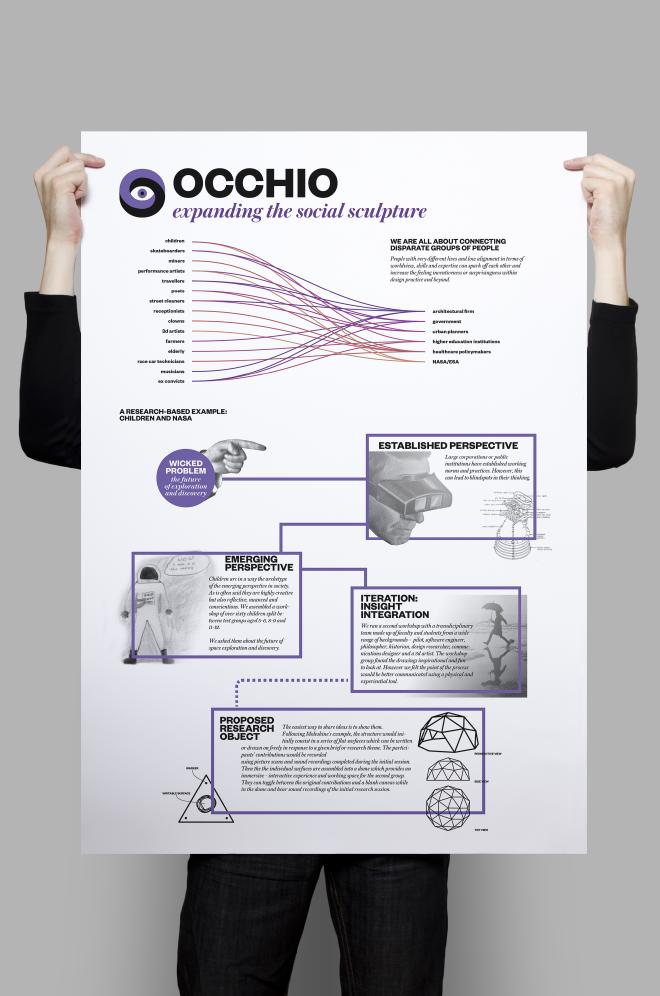

It’s all about connecting disparate groups: people with very different lives and low alignment in terms of worldview, skills or expertise can spark off each other and increase the feeling of inventiveness and surprisingness within a group.

This project started as a research piece on possible methodologies on approaching the unknown unknowns, namely, future wicked problems. An initial methodology was developed, inspired by complex adaptive systems, future forecasting and non-essentialism, especially the open textured concept.

Introduction#

The ideas we would like to explore in this paper centre around wondering what can be done to enrich the work of transdisciplinary groups and designers when they try to engage with how the future ought to be or how to proceed in order to work with the future in mind. We would also like to speculate on how we could humanise social randomness and complexity so it matches up with human needs and desires.

Having outlined this we will then argue that transdisciplinary or non disciplinary teamwork is an essential component in dealing with the often elusive problems that complex adaptive systems throw up. The second half of our paper will then deal with some strategies which we think might be useful for interdisciplinary teams dealing with complex and elusive problems. This will act as both a survey of existing options as well as an attempt to come up with some new processes, methods or creative prompts which might be useful.

As interdisciplinary practitioners we are interested in looking at how design (specifically speculative, systems and post industrial design practices service systems and product service systems) can interact with disparate actors from other fields of study. Our purpose here is not to prohibit team members using insights developed in their respective disciplines. Specialised study and research is important. Instead, we want to try and open up a space for transdisciplinarity for when people with disparate backgrounds need to work together on complex and elusive problems which may emerge now or in the future.

Complex Adaptive Systems#

Complex adaptive systems are bodies of interdependent, dynamic entities and information which exhibit properties and behaviours that are emergent in nature and not necessarily apparent from analysis of the individual parts. A person’s facial structure, which we all recognise and process instantaneously, is an example of a complex system. The nose, eye(s), mouth, cheeks, chin, etc. contribute to something which is more that the sum of their parts. Similarly, both sides of the face look very different when looked at separately. However, when paired they produce a further emergent object which forms facial structure. Facial structures then influence further patterns of behaviour and emergent social properties.

A stronger example of this is in nature, for example when you put hydrogen and oxygen together you get water. Water has properties like wetness which are not apparent in hydrogen or oxygen as parts. There is a kind of “surprisingness” to this emergent information. A pattern that is in the whole but not in the parts is surprising in an information theory sense and predicting that pattern is difficult in a computational sense, put these things together within a system and you get things which you are surprised by.

A complex adaptive system might be a natural, non-human system such as an ant colony or it might be a human system like a human’s immune system or it might be a human made system such as a transport network. Further to this, we might add a fourth category of the artificial system such as an algorithm or artificial intelligence.

A complex adaptive system is categorised by “complex behaviours” which are emergent from “often non linear spatio temporal interaction among a large number of component systems at different levels of organisation”.

X points to a useful definition of complexity given by Rosen and Mikulecky where complexity is the “property of a real world system that is manifest in the inability of any one formalism being adequate to capture all its properties” (page, year). In this sense it’s possible to argue that there is a lack of an essential formalised notion that captures the dynamic of all of the possible interactions with a complex adaptive system. As Rosen and Mikulecky argue the “formal systems needed to describe each distinct aspect are not derivable from each other”. In other words it is impossible to find a universal and formal indicator of how these systems will operate and therefore “distinctly different ways of interacting” with different systems are required.

So, it is possible, combining our outline of emergence and surprisingness and the above definition of complex adaptive systems, to make the following argument. Complex adaptive systems exhibit: (i) an obfuscation of basic cause and effect models, (ii) the patterns or behaviour of the sub parts of these systems is not necessarily apparent in the emergent properties they produce, (iii) dynamic and multifaceted interactions and (iv) strategies for dealing with problems relating to an inability to predict or preempt these “surprising properties” cannot, therefore, rely on essentialist, formalistic or reductivist based strategies alone.

Complex Social Systems#

We live and practice art and design within one subset of complex adaptive systems: social systems. Social systems exhibit emergent properties that are often surprising and are adaptive in the sense that sub parts react to actions by other sub parts and the system as a whole exhibits interdependence between sub parts. Because of these factor cause and effect often seem random. In other words the emergent properties have a certain “surprisingness” to them and the interactions between sub parts are hard to map or engage with. Individuals also exhibit complexity. This follows the argument that individuals are not simply rational homo economicus or an advertising persona. They exhibit the same complexities as the people you actually know rather than those based on abstracted or simplified models.

Systems theory is a vast research area and we highlight it here, in order to relate complex adaptive systems to design and transdisciplinary teams. We will now outline what we mean by those two terms.

By Design we are referring to any design practice which includes a consideration of human interactions with a system. So, the target area is large. Our background is in service, systems, speculative and communication design as well as philosophy and the social sciences. The aim of this paper is to provide, from that initial perspective, a way for transdisciplinary teams to incorporate some of the methodologies and ideas we have picked up from our area of expertise.

The rest of our paper will consist of an exploration of an argument from 20th century philosophy and art which we think is pertinent to the themes we have addressed so far: the open textured concept. Further to this we will speculate in relation to a couple of areas where we think this idea could be developed relating to working in transdisciplinary teams on complex problems.

There is no exhaustive list possible for the things that people from diverse backgrounds can do to work better together so we thought we would offer some that we have found useful throughout our research.

Transdisciplinarity#

One response to the problems created by complex adaptive systems is to problem solve by employing transdisciplinary research and practice. This due to the new kinds of knowledge synthesis required to tackle these problems. Specialisation and mono-disciplinary silos are, in some cases, an impediment to progress.

Mono, multi, and interdisciplinary approaches are valuable producers of knowledge and the latter two allow for interesting cross pollination between defined disciplines. However, transdisciplinarity produces a new way of looking at knowledge communities, working with other people and complex problem solving or responding.

The first thing we’d like to suggest is that transdisciplinary work relies on transjective reasoning. This is where a group is treated as consisting of an open community of inquires and their shared knowledge of the world should work in a way that reflects their characteristics. This might be in the form of taking a transdisciplinary approach or might be termed anti discipline. Either way the collective notion of truth is a pragmatic “truth” and is something that is only approached over time by the open community of inquirers. There may be no immediate solutions apparent but this is accepted because of the nature of dealing with complexity and the surprising nature of the problems thrown up by this.

Recommendations for Transdisciplinary Teams:

- Treat the world as consisting of complex adaptive systems

- There are no totally encompassing solutions.

- Incorporate informal play and imagination into your practice.

- Think about what language or concepts you are using.

- There is much more room for fruitful overlapping between disparate disciplines.

- Be open to new transdisciplinary or anti disciplinary concepts.

- Incorporate insights from outside of the culture of your group.

- Use open source as a metaphor for thinking about transdisciplinarity.

- Refuse to simplify or beautify complex problems.

Another argument we’d like to make is that as an actor within an interdisciplinary team you don’t “just” do anything. In monodisciplinary teams a large number of assumptions are taken to be valid. So for example a group of catholic priests will agree on the general concept definition for “marriage” or a team of engineers might agree on a method of linear analysis of solids and so on. In transdisciplinary teams many similar assumptions, if assumed, will lead to members talking past one another, not being able to progress or even explain themselves easily. This situation seems analogous to speakers of different languages all talking to one another as if each will understand. One response to this might be to invent a metalanguage for interdisciplinary teams or find a quick way of matching or explaining concepts that do not align easily. A metalanguage could be a coded procedural language or could be visual or virtual.

Transdisciplinary teams should be able to speculate, be able to dream and imagine about the present, future or past, think about the human systems they are engaging with and also problem solve, use data effectively and understand the natural facts or social norms related to the problem area.

Transdisciplinary teams might be better situated to deal with human systems by including random citizens in their group work or include people who are from a disparate social group to the members of the team. By this we mean selecting someone randomly off the street or organising a platform whereby the collaboration can take place. This person will not be a surveyed subject or individual data set. Instead they act as a member of the interdisciplinary team. We can imagine a reaction to this: that the person will not be informed! If anything this is a moot point because the nature of transdisciplinary teams is that you might have max one person who exhibits expertise in a given area. What is paramount here is giving the citizen or disparate group a voice and also to show that experts should not always be the sole purveyors and dealers in public problems.

Open Textured Concept#

One argument we’d like to make in reaction to the ideas explored in the first section is that transdisciplinary research and practice can be fruitfully explored using the notion of an open textured concept.

The idea of an open textured concept is a relatively new one, arising out of the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and the art movements of the early 20th century. It runs contrary to an essentialist view of art (and by extension design) which, in terms of the western or european philosophical canon, runs back to Plato.

Plato argued that entities and our perceptual experience of them are split roughly between the following categories: ideal (idea) , object and picture. Under this argument art is always three steps away from idea and is tied to aesthetic perceptual experience or more importantly - limited to aesthetic experience. This is what we mean by an essentialist view of art. Taking essentialism as a general position we can say that it implies the ability to deduce that something is art or design based on its reducible properties. There is a ready made solution to the question what is art? Namely, that is something which is based in a purely aesthetic appearance: “the painting was beautiful” or “I fell in love with the curvature of the sculpture, it was fantastic!”. This essentialist view carries forward to Clive Bell, an English critic associated with formalism, for example in his 1914 work entitled Art. Within this he argues that when we look at some artistic object compared to some other non artistic object say a cup of coffee or a pen we have a distinct aesthetic experience relating to the artwork and not to the non artwork. This, he implies, means that the artwork can be explained as having a significant form while the cup of coffee or pen are not in possession of this significant form. We can say that Bell’s significant form occurs when an entity is structured, in such a way, so that their arrangement provokes an emotional response in the viewer which is particular to the object. You can’t necessarily show significant form but the key relationship is between the triggering of an emotional response to the particular structure of colour, shape etc.

Given the 21st century’s inheritance and normalisation of modernist and post modernist arguments about art and design, we will quickly sketch out some interesting aspects of this change and then explain the idea of the open textured concept. According to Bell, if there’s content outside of the aesthetic experience then it does not count as art. If the object is the coffee cup or the work is overtly political than the work does not count as art under Bell’s terms.

One major reaction to this is something like Marcel Duchamp’s anti-aesthetic or anti-retinal art. Which is centred on the question of what is it, apart from aesthetics, that makes something a work of art.

One aspect of art is, quite obviously, that they are made by artists, appear in art institutions, have titles not names and it might require that an expert say it’s a work of art and if they do then that means that it probably is a work of art. You might go visit a doctor when you are sick in the same way that Duchamp would suggest that you go see an art expert if you want to check if something is a work of art:

A: Made by an artist. B: Appears in an art institution. C: Has a title not a name. D: If an expert deems it art it probably is art.

E: ? (Some further extension of the concept or an argument to challenge the previous assumptions).

A philosophical analogy can be made here in relation to the later writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein counters (over the course of Philosophical Investigations (1953) ) an inherited notion, from the history of philosophy, that we can know the “essential” identities of things through disambiguation between those entities “essential” properties. So, for example we can tell the difference between a camel versus a cow versus a train because each has a central “essential” definition which distinguishes it from another and this has been internalised. Platonic form is an example of this idea where each entity is related to a perfect form “the cow” and so on with deviations within that concept apparent in the individual.

In order to challenge this kind of argument, Wittgenstein, makes use of the concept of a language game and convention. He asks the question is there an “essential” quality, that without which a game would cease to be a game? There are games that we play outdoors and indoors, games that include balls and games that don’t and so on. He argues that, therefore, there is no “essential” definition for a game. Instead what games do have is family resemblance. We can list these resemblances and we can make inferences based on these resemblances. So, for example we can look at cousin John and say that he reminds us of aunt Betty or that football reminds us of rugby and so on. (The inexhaustibility of the related qualities of games means that there is no central, “essential” conception of them available). In this case concepts cluster around certain resemblances without there being an “essential” definition or central reducible aspect.

An relevant application of Wittgenstein’s game theory is in defining art. Applied to art his theory of games would look like this: were we to search for one thing common to all work works of art we would find that while there isn’t a single characteristic common to them all,they do share likenesses or resemblances. For example were I to put 100 different objects in a room and only one of them was a work of art, another person would probably be able to pick it out because she recognises the necessary conventions that comprise art’s identity, i.e. a frame and paint on canvas.

Morris Weitz writing in (Weitz, 1956) attempts to deal with the problems relating to the question “what is art?” which became apparent as a result of modernist unconventionality in relation to older more traditional works. A reformulation of the requisite categories of art, in line with Wittgenstein’s arguments above, was centred around the idea that art was a sort of open concept. That is to say that it is non “essential” and without necessary and sufficient conditions which are tied to aesthetic experience alone. A central argument Weitz makes is that we learn the right use of words and concepts relating to entities through observing how others use the word in certain situations. That is to say, that we learn by playing a language game about the supposed objects of art and that our conception of art (and our ability to pick out the art-object in the room of 500 objects) is based on an inference from those linguistic and social conventions.

Works of art, then, are part of a certain collation of a particular kind of collection of objects and traditional aesthetic theories of art are based on a false logical premise because it is not possible to isolate the necessary and sufficient conditions that make up a work of art through aesthetic experience alone. In this sense the category of art might be said to be non tautological or in Wittgenstein’s terminology: “nonsense”. That is to say that it is neither related to natural facts which for example the sciences might try and discover. Neither is it related to tautology or logical and mathematical reduction. Instead because of the lack of necessary and sufficient conditions for works of art the category can be said to be an open and inferential concept.

Weitz’s notion of an open concept is:

A concept is open if its conditions of application are emendable and corrigible; i.e. if a situation or case can be imagined or secured which would call for some sort of decision on our part to extend the use of the concept to cover this, or to close the concept and invent a new one to deal with the new case and its new property. (Weitz, 1956 , 31)

A closed concept is one in which:

[…] necessary and sufficient conditions for the application of a concept can be stated, the concept is a closed one. But this can happen only in logic or mathematics where concepts are constructed and completely defined. It cannot occur with empirically-descriptive and normative concepts unless we arbitrarily close them by stipulating the ranges of their uses (ibid, 31). By giving an “essential” definition of art you are closing a concept which is an open concept. In other words, art does not have ubiquitously transferable qualities that can be picked up from one set of things and linked, via an “essential” definition of the form “art”, to another set because there are no necessary and sufficient conditions for that definition.

There are a number of problems with this argument such as: (i) Wittgenstein’s idea that use is the main criteria for a concept, specifically use related to linguistic use and concepts. (ii) We, roughly speaking, share a conception of art such that, in the very least, we know what we are talking about when we mention a renaissance painter and a post-modern artist in the same breath.

Given that (i) is based on Wittgenstein’s full argument outlined in Philosophical Investigations it can be left aside here. The counter argument in (ii) is more easily dealt with because, we can assume, that Weitz’s point relates to non “essential” and therefore ubiquitous definition exists for art. In other words, there is not a closed set of concepts and related necessary and sufficient conditions from which we can draw in order to uncover a real definition for art.

Taking up this argument, we would like to maintain that open textured concepts are an important asset for not just those thinking about art but also involving design (the link here is pretty obvious), social behaviour, transdisciplinarity and potentially beyond. We’ll refine what we mean by giving an example related to art and then try and repurpose this for the other categories listed. In addition, we want to suggest that there are a cluster of methods, concepts and ideas that are interdependent with the open textured concept and that these form a useful partnership for design and transdisciplinary teams when attempting to deal with complex problems. We think that open textured concepts are a way of thinking about and managing complexity which might be a useful starting point for those trying to plan, react to or design for complex social, environmental or human problems which may not have solutions which are apparent or readily available.

Chris Burden’s piece “747” involved the artist going out onto the runway at LAX and firing bullets at a Boeing 747 taking off. The immediate question here is whether this can count as a piece of art? There’s a preponderance of evidence to suggest that it is but there is no guaranteed that it can count as a work of art. In a later work Burden tasked a man with a sniper rifle to shoot him in the arm. Again the question remains as to whether there is any meaningful or reasonable information that can be used to infer that Burden’s activity can be included in the convention of what counts as art?

So, lets check:

A: Is made by an artist? (Y) B: Is displayed in an institution? (N or at least not directly) C: Has a title not a name? (Y) D: Is deemed to be art by an expert? (Y, although this might be changed to “by at least one expert”)

So, given the open concept argument we can add another category for both works: E: New quality of art: e.g. shooting at 747 or enlisting your fellow man to carry out attempted murder on yourself.

E throws up all sorts of definitional problems which can be said to be apart from any “facts” of the case. Further to this, it’s not apparent as to whether there is an exact solution to E. Or at least it’s easy to imagine how a hypothetical argument or negotiation (say between Clive Bell and Burden) over E might proceed but very hard to see how it would be resolved. Therefore, the solution to E is not apparent based on any facts of the matter, any “essential” form we can point to nor based on logical inference from aesthetic experience. If this argument is right, then, it opens up some interesting possibilities for those areas of art and design which try to solve complex problems outside of the traditional borders of those disciplines. Next, we will outline a couple of ways this could proceed in relation to the concept of emergence and “surprisingness” in complex adaptive systems and strategies for dealing with the wicked/complex problems those systems throw up.

Potential Extensions of the Open Textured Concept#

An interesting extension of the idea of an open textured concept is an argument emerging from meta metaphysics and ethics. Philosophers such as (Amie Thomasson, ) and (Plunkett and Sundell, 2013) are exploring how the sorts of debates over definitions, concepts and language rather than facts impact on how we conceptually sort out and disagree over social categories and norms, ethics, categories of scientific classification and also themes relating to Weitz’s initial argument relating to works of art and design.

For example, New York City recognises 32 separate gender identity possibilities (ref). Presumably, someone in New York still believes that there are just two possibilities: man and woman. Our interpretation of conceptual ethics, following the idea of the open textured concept, is that it is chiefly concerned with mapping the definitional, conceptual and linguistic debate between these two (or more) potential divergent positions and then using that map to better understand the kinds of “first order” ethical debates people have relating to what is or ought to be the case.

(Plunkett and Sundell, 2013) argue that these two hypothetical parties: the city of New York and the person who disagrees with their position on gender are engaged in a dispute not over the facts of the case but rather one that is definitional. Using their terminology the parties are involved in a “metalinguistic negotiation” (2013, 3). This is “disagreement (which) is reflected in such a linguistic exchange..(via) a largely tacit negotiation over how best to use the relevant words” and what sort of metalinguistic usage the term should subscribe to in that given context (3). This relates to exchanges where the terms “meta linguistic usage” where “linguistic expression is used (not mentioned) to communicate information about the appropriate usage of that very expression in context” (3). They describe this process as a metalinguistic negotiation which has two elements: (i) a mutual sharpening and negotiation of the metalinguistic usage in question between users and (ii) the normative question of how best to use a concept relative to a particular context. This way of looking at disagreement is pertinent to exchanges where there is an indeterminacy antecedent to the particular dispute which applies to what we have discussed so far in this paper.

The point for designers and those working in transdisciplinary teams is to both internally (within the working group) and externally (in the world outside the group) acknowledge this aspect of how we rationalise and think about our assumptions about what should be the case and how this contrasts with others.

We want to argue that these sorts of groups ought to keep in mind the following steps when dealing with divergent ideas or assumptions:

A. (Internally within the group):

(i) Temporarily disallow for the idea that there must be some fact or truth hiding behind the divergent ideas. The meanings involved are related to convention, usage, x’s language and concepts in divergence to y’s language and concepts.

(ii) Try and sort out if there is actually divergence by using paraphrase (Chalmers, 2011), if the paraphrase does not lead to a change in the divergence then map out the real and substantial differences so that parties are not merely talking past each other.

(iii) Try and use another way of representing the information e.g. through colours, drawings or again by paraphrasing the language that you are using to convey your point.

(iv) Finally, if the divergence is real and substantial then allow it to exist like that and move on. The allowance for this might lead to interesting solutions later on.

B. (Externally: When Trying to Categorise the Complex Social Systems you are Designing for) (i) Map out the conceptual possibilities for some target groups or topic such as gender or works of art. Temporarily disallow for truth or notions of wrong and right relating to the respective groups.

(ii) Again, try and sort out the extent and nature of the divergence by paraphrasing the language and concepts in question. This is to ensure there is actually some real divergence rather than superficial or “merely verbal”, in Chalmer’s (2011) terms, disagreement or divergence in question.

(iii) Try and represent the information through data, visuals (abstracted such as a drawing or painting or using clear visual information). Then reflect on how this might allow for a new paraphrase or insight on the original problem.

(iv) Again, if the disagreement or divergence is still apparent then it is real and shouldn’t be challenged further.

A similar idea has been popularised recently in the form of people exhibiting a bias. The problem with using this term and its related ideas is, for us, that it implies that people should necessarily repress and control their bias or propensity to believe x. Conceptual ethics is a much more flexible and open way of addressing some of the problems people associate with biases but without making the process inherently political or introducing a need to repress the things people really feel ought to happen. In our view conceptual ethics gives a framework for discussion and exploration rather than presenting a need to “check your” biases if a majority of people in a group do not share the same assumptions. In other words, it allows for there to be real disagreement where it might actually occur and tries to prevent against individuals talking past each other when real disagreement is not apparent.

Methods for Trans-Disciplinary Teams Deling With Complex Problems#

On the 3rd of December 2016 we conducted a workshop to trial some of our ideas and methods within a transdisciplinary group. Our group consisted of persons from the following backgrounds: philosophy, computer science, art, design, communication design and history. The following were methods that we trialled:

Oblique Processing#

Another important element in thinking about and using open textured concepts is being able to stimulate discussions which can lead to potential changes of convention or thought in relation to A-D and also generating new possibilities for E. One method we found useful for this was trying to find ways to generate ideas obliquely or by avoiding linear reasoning. Using Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies as a template we came up with a set of prompt cards which specifically deal with complex problems, possible worlds and our human perspective on both. We included a number of blank cards, on which participants could write in their own questions. The point of this is to induce oblique processing within teams. This is useful because it allows individuals to offload their rational thinking to prompts or questions which then (hopefully) stimulate invigorating discussions or ideas.

Find a Random Input#

In our case we choose to use children’s responses to questions about the future of exploration and discovery in order to stimulate thinking in an adult research group. There are countless other ways of trying to achieve this effect.

For example you might link with players of virtual reality games or you might enlist a random person on the street.

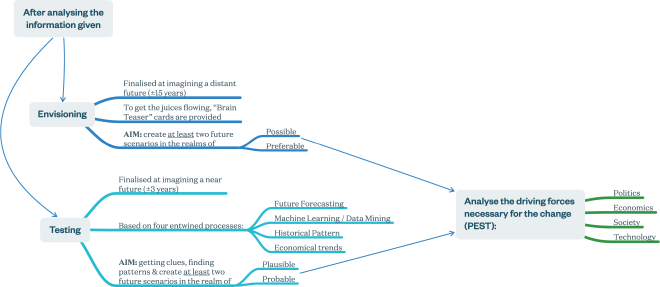

Possible Worlds#

We can split the present into the following variables: time (t), person (p), world (w), context (c).

We can then change all of the variables in order to imagine some possible world (pw) where some things may be different and others not. Participants were asked to insert and then change a variable in each of the above constraints in order to come up with an imagined possible world. The point here was to show how the constraints can be used to come up with ideas and imagined outcomes or possible worlds.

What is the symbiotic potential of the focus of your work within current or possible systems?#

X + Y = ? (is x symbiotic with y? Will it logically/plausibly fit?). In other words what is the likelihood of x and y being amenable to symbiosis? We asked participants to assess how symbiotic their projected outcome was in relation to the present. The present or current system, here, might refer to normative facts, natural facts or general subjective observations about the way some set of relations works. For example, how symbiotic is the idea that robots will replace teachers to the way the education system works today (quantitative, qualitative or subjective observations). The point of this is to think about how amenable the projected outcome or idea is to symbiosis given what is the case or what might be the case at the present time. The term “symbiobility”, or amenability to symbiosis is, according to our purposes, the ability for one thing to enter into symbiotic union with other entities.

Think about whether the focus of your work is Raw or Cooked:

We asked participants to reflect on specific data sets (in the test case these related to the future of education) and their ideas using a simple two part classification: the raw and the cooked. This exercise is based on Claude Levi Strauss’ idea contained in The Raw and the Cooked (1964). Extrapolating from his writing we used it as a metaphorical device in order to check the dynamic for a proposed change in a system relating to whether it seemed: new/old, subcultural/mainstream, emergent surprising/emergent recognised and/or fresh/played out.

Open Textured Analysis#

We asked participants to list A-E what the characteristic of some x was. A problem example might be the status of the university.

A: A place for learning. B: A place to experiment. C: A place for meeting new people. D: A place to research what really interests you.

E: A Business?

Dynamic Outcomes Mapping for the Focus of Your Work#

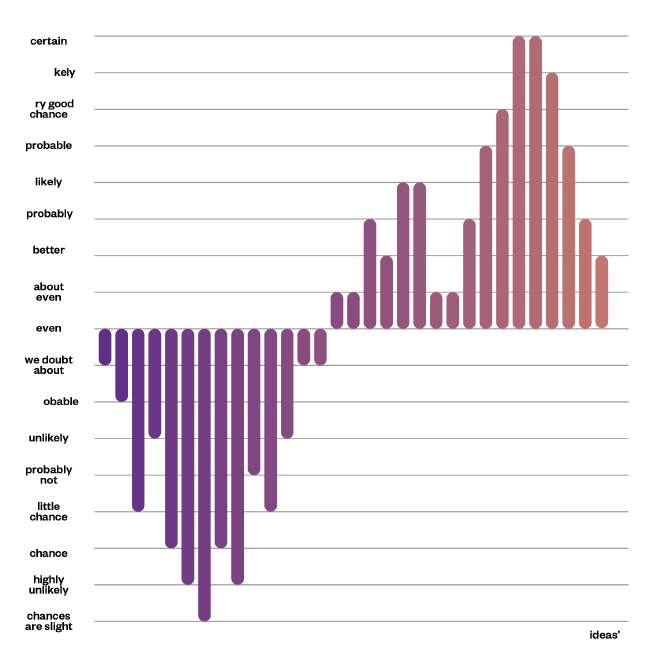

Is it almost certain, highly likely, very good chance, probable, likely,probably we believe that, better than even, about even, we doubt that, improbable, unlikely, probably not, little chance, almost no chance, highly unlikely, chances are slight?

We asked participants to respond to the test data/ideas/arguments using the above outcome variables as guides. The goal here is to match outcomes of the future of x to the outcome variables in order to see how likely a given scenario is. Participants were able to match to as many or as little variables as they liked. If they disagreed, say because the variables were to simplistic, then we asked them to match to the closest one and give a further explanation as to why this was wrong.

Counterfactual Analysis#

- Large non discrete counterfactuals: Choose a different system, what does the problem look like in that system? So for example what does the university look like now if the western world adopted a post capitalist economic model in 1995.

- Creative counterfactuals: We asked participants to come up with a future timeline and -30 year history prior to the present: -30, -15, 0, 15, 30, 90, far future. Then we asked them to change -30 and -15 and map out how this would change the previous future timeline.

- Discrete counterfactuals: Pick a small change in a system and speculate how that might change history. Think about how its discrete, emergent from what? and/or surprising.

Disparate Group Analysis#

Take two social groups which are very different in nature and look at their responses to the focus of your work. We used the examples of children (5-6) and (11-12) and compared this to a similar set of questions asked to a transdisciplinary adult group of 23+.

Ethics#

What are the ethical problems relating to the causal interaction of your focus with the world? What theoretical constructs do we think best account for what we ought to do? What is preferable? What relationship does our argument have with law or economics or politics? How do your arguments here relate to conceptual ethics?

Cultural Analysis#

Look at the focus of your work through the following lenses:

- Subculture (outlier) analysis + story

- Dominant culture (regime)

- Popular emergent culture (imposter)

- Structures of power and implementation (how change happens).

Our Framework#

Bibliography#

Bell, Clive. (1914). Art.

Chalmers, David. (2011). Verbal Disputes. Philosophical Review. 120 (4). 515-566.

Honavar, Vasant. Complex Adaptive Systems Group at Iowa State University, http://www.cs.iastate.edu/~honavar/alife.isu.html, (date accessed: 7 December, 2016).

Levi Strauss, Claude. (1964). The Raw and the Cooked.

Mikulecky, D. 2001. The Emergence of Complexity: Science Coming of Age or Science Growing Old? Computers and Chemistry. 341-48

Plato. Translated by Alan Bloom (1991). The Republic.

Plunkett, David & Sundell, Timothy (2013). Disagreement and the Semantics of Normative and Evaluative Terms. Philosophers’ Imprint 13 (23).

Weitz, Morris. (1956) The Role of Theory in Aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 15, No. 1. (September), pp. 27-35.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1953). Philosophical Investigations.